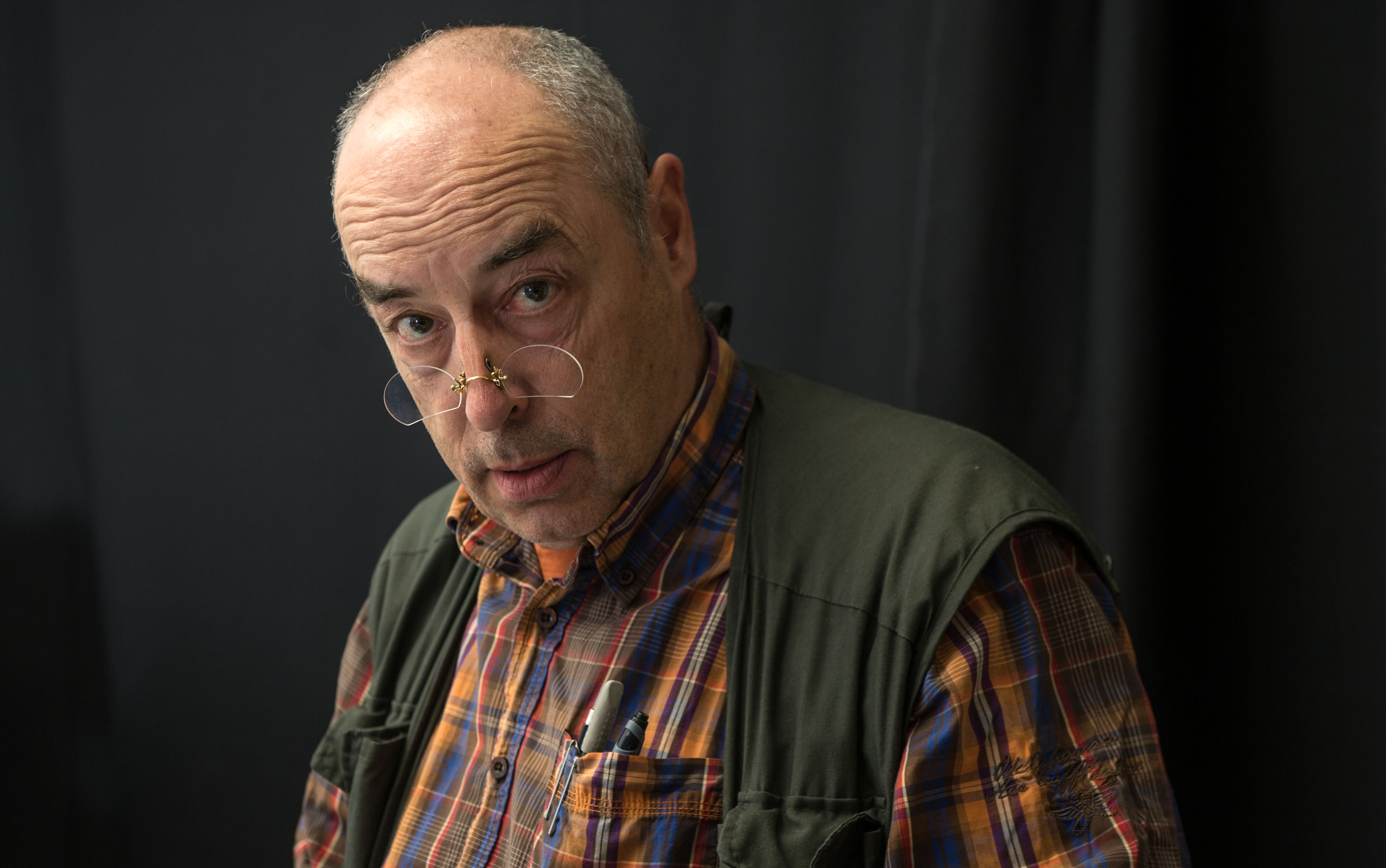

Ludwig Oechslin interview

| Cail Pearce

Beat Weinmann: “This is the interview from which I learned the most about Ludwig in my 15 years of working with him.”

The interview below was conducted by Ralph Hubacher, the host of Inspiring Podcast. The translation/summary was produced by Claudia Walder. You can also listen to the German original.

Translation/summary

Interviewer: Welcome to Inspiring Podcast, today I am in Ludwig Oechslin’s atelier at ochs und junior. Dr. Oechslin, thank you for taking the time. Let me introduce you really quickly to our listeners: you went to school in Lucerne, studied ancient history in Basel, and hold a licentiate degree in Archeology, Ancient History and Ancient Greek. However, parallel to you studies, which you continued in Bern with Astronomy, Philosophy and the History of Science, you learned a very special craft: watchmaking. Until 2014 you acted as director of the renowned Musée international d’horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Before that, you also worked as developer – inventor is perhaps too vague a term – for big watch brands like Ulysse Nardin. And 2006 you founded, or cofounded, the company ochs und junior. What I find particularly fascinating is that you do the opposite of what most people would do in this position. Most people would build more and more complex watches and you simplify the whole thing down to its essence. I read a very simple question that you’ve written: for what purpose does one need a watch? So my simple question to you, Dr. Oechslin: for what purpose do you need a watch?

Ludwig Oechslin: A watch is basically like a calendar. If one were on one’s own, one wouldn’t need a calendar. You need calendars to organize things with each other. To meet up at certain dates, to fix business meetings and so on. A watch is the same but for a smaller timeframe. Instead of helping you getting organized across several days, it helps you with getting organized within one day. You meet up for lunch or similar. If you don’t want to miss each other, you need some kind of instrument to communicate with each other and to keep your appointments with each other. The convention is to take the earth’s rotation as a basis, and separate that into 24 hours, and that’s a given. So basically, what we are wearing on our wrists is a little earth.

That’s an interesting aspect. What about today though, are watches still needed? I was born in 1974, I still see the necessity for a watch, but what about someone who’s born in 2004? Does the smartphone replace the watch?

No, no, it’s basically the same. It doesn’t matter whether you have a display that shows 12:30 PM or a minute hand that points downwards and an hour hand that points upwards – that’s analogue, but it’s basically the same. You may not have an analogue watch on your smartphone, but you still have a fixed scale of 24 hours. And there are even smartphones that show an analogue watch face instead of the digital display with numbers –

You can set that in your preferences, can’t you?

– yes, and I know many people who prefer that their smartphone show the analogue dial.

And that’s faster, I mean the analogue display?

Yes, because with the digital display, you first need to read the numbers, and then you need to figure out their meaning.

Speaking of meaning. Do you remember the very first watch you owned?

I don’t precisely remember. I guess I received some kind of watch for my confirmation. I rarely wore a watch, because from the age of 14, I grew up in a boarding school. There, time was indicated by the bell, so you knew exactly when an hour had passed, when you had a break and so on. You didn’t need a watch. The need for a watch only arose when there were no longer any bells: at university. It was there that I realized I needed something to indicate the time, to make sure I was on time for my lectures, though I knew I didn’t want to wear a wristwatch. It had to be a pocket watch or something like that – smartphones didn’t exist at the time. So I went to the first Arts and Antiquities Fair in Basel in 1973, in spring. At one of the first stalls I found a watch that still rang. That absolutely fascinated me, though my budget couldn’t cover something like that at the time. So I had to content myself with something cheaper. But ever since, I have kept buying and exchanging pocket watches.

How did that fascination with watches come about?

The first watch that really fascinated me was that watch I just mentioned at the fair. You could pull a little lever and it would repeat the quarter hour – or the minute, I don’t remember exactly. I really wanted that kind of watch. It would have been a parallel to the bell I knew: you could have heard it ring the quarter hour even in your pocket and you wouldn’t even have to take it out and hold it before your eyes. That was one thing, the other was that it was just fascinating that something like this was possible on so small a scale. Today, of course, something like that seems natural.

You studied first in Basel, then in Bern. But in parallel, you started a watchmaking apprenticeship. I know very few people who graduate with a PhD and still learn a craft. How did that come about?

Well, I started my studies to acquire a sort of general education, to get to a certain level of general knowledge. That was without aiming at a specific profession or source of income. But at a certain point, I had to think about how I would earn a living. Plus, when I first started my studies, I wasn’t very successful, so I had to think about whether I had the intelligence, the brains to study at all. I then immediately started to look for something else that I could do and soon settled on an apprenticeship for a craft. Because I always tinkered with precision mechanics, I figured that goldsmith or watchmaker would be just the thing for me. Of the two, I felt more drawn towards watchmaking because of its theoretical background in physics and mathematics. I started looking for an apprenticeship and a master watchmaker who would take me on. That was pretty difficult, because it was extremely unusual at that time to start on a second path. And most masters who normally had 16-year old apprentices were really skeptical of me.

How old were you back then?

Well, it was after my “Matura” (Swiss university entrance exam) and after I had already started my studies. So I was about 22 and people thought I was out of my mind. At the end, I found Jörg Spöring in Lucerne and started negotiations with him. In the meantime, my grades at university got better and I decided to complete my studies. At the same time, I was determined to go forward with the apprenticeship I had set up by then. And since I started actually liking the scientific method at university I just went ahead with both of these paths.

That sounds pretty demanding.

It wasn’t really that demanding. It just happened that way. I never tried to get everything done at the same time, not at all. I just had fun doing it.

Later, you became a developer at Ulysse Nardin. I heard that you were behind the Freak and were also one of the minds behind the Türler clock. How does one come up with such crazy ideas, if I may phrase it like that.

I had agreed with Jörg Spöring that I would not be doing just petty apprenticeship stuff, but that I could work on projects designed to bring about progress in the craft. And the term watchmaker means making watches. My goal was always to develop my own watches one day. To create your own watches from beginning to end was not a given back then, because the craft of watchmaking was in a crisis. That had only partly to do with the watch and the quartz crises, but also with the industrialization of watchmaking which had begun. Subsequently you had very specialized watchmakers in the industry, who could only operate one or the other specific machines, making one specific part for the watch. But finding someone who could build or manufacture an entire watch from scratch, with all gimmicks, that was rare. Watchmaking as a craft actually had to be reinvented in the 1980s and 90s. Several people actually drove that development, they organized themselves for example in the Academy of Free Watchmakers, which still exists by the way.

And you are a member of that?

No, I was not a member of anything, that’s just not my character. Anyways, once you start making your own watches, you have to master everything, from the construction to the combination of materials to the combination of all of these things. And that automatically prevents you from doing things the same and leads you to do something new. It also led to my first collaboration with Jörg Spöring, a large pendulum clock with an astrolabe. The transition rates needed interested me, just like the question: how do you make a good pendulum clock? And along came Rolf Schnyder, who had bought Ulysse Nardin, and wanted that clock for his wrist. It wasn’t a question of how to come up with it, it sprang from the situation. Then I thought, it would be a pity if Ulysse Nardin only had one astronomical watch. I had already studied a number of watches, especially historical watches, and thus came across certain constructions. One example is Bürgi’s planetarium in Vienna which features a fixed axis sun-earth but still has the planets turning around the sun. I used that system to build my planetary watch for Ulysse Nardin. I felt that gives you an overview. Then there’s the view from earth. So then, there’s the third, partial viewpoint. That’s the tellurium which shows the relative motions of the sun, the moon, and the earth. That completed my trilogy for Ulysse Nardin. But those are not ideas that just spring from the air, or where you sit down and say: I have to come up with something new. These are all developments that are based on existing systems, but combined in new ways. Though it may look like these ideas just fall from the sky for someone who has no insight into this process.

Yes, it certainly looks that way to outsiders! That’s the classic sense of “innovation” – from Latin “innovare”, meaning finding, not inventing.

The problem is, inventing and innovating are two completely different things. When inventing, you may just randomly happen on something that inspires the right idea. It may be something fairly new, but it doesn’t come from nothing. Of course, I have occasionally used random finds as well, but these did not just appear from the void either. They had been there before, but I suddenly understood the connections. That’s what it’s always about: understanding the connections. But then, a new product is only an innovation if it is successful. Because innovation is definitely tied to success. An innovation may be an invention, but it doesn’t have to be. There are innovations that have existed for a long time before they get any traction due to historical circumstances.

Stephan Hawking said in one of his final messages: Be curious, stay curious. Would you say that you’re a curious person?

Yes, certainly, that’s the driving force behind everything, curiosity. If you don’t keep asking about this and that and everything, you won’t make any progress.

Then all you do is work according to rules, basically. Which certainly doesn’t apply to you – especially when I look at the watches here on the table. You know my favorite watch, the perpetual calendar – to all listeners, check it out on the website, it’s just a gorgeous watch. And I know that there’s a huge development effort behind this watch – four years, I read somewhere, but in our preparation talk you corrected me and explained that there’s several decades of work behind this watch. The special thing about this watch is, well, Patek Philippe needed 182 parts I believe to execute that function and you turned that on its head, you just needed 9 parts. That seems almost impossible.

Well, the issue is a different one. The normal perpetual calendar, as it was developed in the 19th century, basically consists of a lever that swings back and forth to a smaller or larger degree, and based on that smaller or larger movement, it then skips less or more days at the end of the month. This lever is controlled by a program wheel, into which it can enter to a smaller or bigger degree, and this program wheel turns by 1/12 of a full rotation. The depth of the indentation on the wheel determines how many gear teeth the lever can skip at the end of the month. The problem was actually, Jörg Spöring gave me a perpetual calendar, during my apprenticeship, which had gone through the hands of seven watchmakers and still wasn’t working. So I had to occupy myself with that construction and I realized that many of the problems perpetual calendars have, stem from the motion of that lever. The construction is not a convincing one because one, it’s based on a lever, and two, it allows for only one direction when setting it – so if you overturn it, you’ll have to turn through another four years and that of course is a strain on the whole mechanic system. I was amazed that in the more than 100 years that this function has existed, no one has improved the construction to avoid that problem. I thought that it somehow has to be possible to overcome this difficulty. Nevertheless, the function is fascinating with its whole mathematical background. So I revised that calendar and then wanted to make my own calendar watch. One because of the whole theoretical background and the difficult mechanics. And two, because when I studied early calendar watches, I found that at the beginning, when the perpetual calendar was first developed, there were still several construction principles in use. Philipp Matthäus Hahn for example used a rotation principle. I thought, for my own calendar watch, I had to find a solution that was not based on levers and focus on solutions based on rotation instead. These ideas started in the 80s and continued to develop from there. I probably drew up fifty or more different constructions for perpetual calendars. What we have here at ochs und junior is the final product. In the sense that the construction is at a point where I’m happy with it. At the moment, in any case. One approach is to solve one problem or task after another, but you can also try to solve several problems with one part instead of solving each problem with yet another part. In other words, find a synthetic solution instead of an additive one. I really wanted to find a synthetic solution. Perhaps that is psychological, because it’s a bigger challenge. And it apparently takes decades of continuous improvement. Additive solutions are easier, I could always have found additive solutions. However, I try to look not at a problem in isolation, but to look at the whole mechanism. So I think about how to improve the whole. In that way, you can save parts, but you can’t save work. Because the effort in the theoretical area, thinking of new solutions, trying them out, improving them, is much larger than with additive solutions. This preparatory work is very complex and diverse. So it’s not about finding simpler solutions. The solution is actually very complex, but it’s executed in one part. That’s much more complex than what other do. The other issue is that each part you use is a potential source of error. Always. Think about it, all these parts need to communicate, each wheel has to interlock with another. If you need two wheels interlocking for a transition, that’s one potential source of error, but if you need five wheels interlocking to execute a transition, then I have five sources of friction and error. I can minimize that and thus make the function more reliable. That was the second goal. The third goal – although that’s not actually a goal – are the limited resources and tools I have at my disposal when building prototypes. So I have an interest in having to create as few parts as possible. It’s not like when you have machines that can just spit out whatever parts you need. When you have to manufacture every single part yourself, then you know that each additional part you have to manufacture will prolong the process. In my atelier, I have a milling machine, I don’t have a 3D printer.

When we started talking, you warned me that if I ask you a question, I will have to “endure” the answer. So, I have to ask: the term “simplicity” is on everyone’s lips at the moment, in industry, in management. The world seems to get more and more complex and people seem to try to simplify their lives again in many aspects. What are your thoughts on that subject?

It can’t be the goal to make something simple. That’s not possible, that’s like plucking ideas at random from the sky.

Are these hordes of managers on the wrong paths then?

Well, perhaps it helps them cope, psychologically, with certain things if they think they are simple. Human beings live in their own minds, in their intellects. Most of what we imagine the world to be is just an idea, a concept. And if someone feels good about the concept of something being simple then that’s ok, I can accept that. It doesn’t work for me though – for me, personally, it’s nonsense. Though it can have a positive effect, like religion can have a positive effect. Now, my mechanisms may look simple from the outside, because there are less parts, but these parts are fairly difficult to understand, they are very complex. But the watch is simpler to manufacture with less parts. It cannot therefore be cheaper though, because you have to factor in that lengthy and complex development process. People don’t always see that and then say: oh, I could have come up that, too. Take the date spiral, for example. It consists of 31 holes, but spirals out ever so slightly. So the 31st comes to sit right above the 1st hole. In that way, you have a division of 30, which no longer conflicts with the division of 60, and you can use the 10-minute markers as 5-day markers for the date. And I can use the same analogue display that I use for the time for the date. So my date display is analogue, even though it goes up to 31. In principle, it’s stupidly simple: I use the exact same date disc that you find in every watch and that rotates in 31 steps. Only on the 31st, the dot falls down to the 1st because of the shape of the dot. So it’s purely a design solution. But to arrive at that design solution I had to try out countless mechanical approaches, trying to unite a division of 31 with a division of 60.

Isn’t that extremely frustrating sometimes, when you try something out only to completely dismiss it?

No, because each development is necessary to arrive at the next one. For me, at any rate. There have been a few dead ends, of course, but each dead end has yielded some knowledge, which has led to progress on the right path. You gain experience with every part that you make and that always contributes to the solutions that work, in the end. That’s why there are no real dead ends for me, in that sense.

That’s a valuable point! Our time is almost up, but I still have one more question: You are Lucerne native, do you have any tips for our listeners? A good museum, a good book, or restaurant? … besides the Musée international d’horlogerie, of course.

Well, the Musée international d’horlogerie is probably the most important one, globally, for the history of timekeeping. Especially after the Museum of Time in the USA closed down in the 1990s. There are institutions in other areas that are just as important in their field, like the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza, which has wonderful things.

What about books?

Perhaps Juanito Martorell, Tales of the White Knight. It’s a book I didn’t come to know directly, but of which I took notice of while reading Don Quixote. In Don Quixote, his library is destroyed by one of his friends, because it is seen as the source of his madness. That scene is Cervantes’ opportunity to critique the literature of his time – and in the story, only one book escapes destruction: Tales of the White Knight. At first I thought it was a made-up book, but the book actually exists, it’s by Juanito Martorell, and it was written about 100 years before Don Quixote. I think it’s one of the best books to get into!

What about culinary tips?

Well, the problem is I love spaghetti carbonara. But here in Switzerland, people think spaghetti carbonara is something that involves bacon and lots of crème. In Italy, I got to know a different dish. “Carbonara” actually means burnt, black. It doesn’t refer to the crisp bacon, or pork rind cubes. It refers to pepper. And in Italy, you actually use so much pepper for the dish that the spaghetti looks black. And there is no dairy product on it but cheese, mixed with egg yolk. So you keep your guanciale on the side. You put the spaghetti in the bowl with the cheese and the egg yolk and the pepper, and you add some of the water you cooked the spaghetti in. You then mix everything. It doesn’t matter if there’s a little too much liquid in the beginning, it dries up quickly.

Wow, I didn’t expect a cooking lesson today … we are at the end of our podcast. Thank you so much for you time, Dr. Oechslin, and for an inspiring and fascinating talk!